Embracing Neurodiversity in the Workplace: Benefits, Challenges, and Best Practices

Neurodiversity in the workplace is grossly underrepresented in the American workforce. Too many organizations have focused on the perceived challenges of embracing neurodiversity in the workplace, while too few businesses have acknowledged the remarkable abilities and superior work ethic that many neurodivergent people can bring to the job.

It’s important to acknowledge that different types of diversity exist in order to create workplaces that are truly inclusive.

Read on for a deep dive into why neurodiverse employees’ unique skills, from their diverse perspectives to their creativity, can benefit any organization.

What is neurodiversity in the workplace?

Neurodiversity is a concept that recognizes and values the diverse range of neurological differences among individuals, promoting the idea that variations in the brain's functioning are a natural part of human diversity.

The term "neurodivergent" refers to individuals whose neurological development and functioning differs from “neurotypical” people, encompassing conditions such as autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and other cognitive variations.

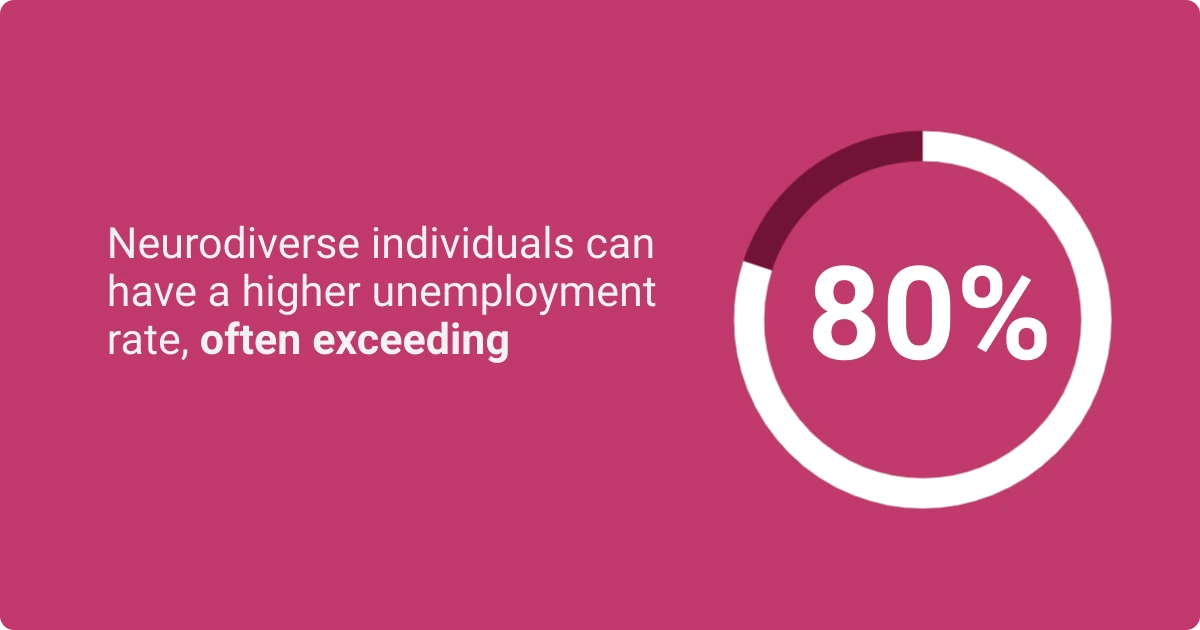

The term "neurodiverse" encompasses both neurodivergent and neurotypical individuals, highlighting the richness that diverse cognitive styles bring to a work environment. While approximately 15-20% of the population is neurodivergent, many face significant barriers to employment. A study by Northwestern Medicine Opens in a new tabshows that neurodivergent individuals often experience an unemployment rate exceeding 80%.

By embracing neurodivergent employees, organizations can unlock their unique talents and perspectives, fostering innovation and enhancing team performance.

Examples of neurodiversity in the workplace

Neurodiversity includes a range of neurological differences, with common conditions such as autism, ADHD, and dyslexia, each bringing unique characteristics and strengths to their roles.

Autism can manifest in a variety of ways, but it often causes differences in social interaction, communication, and sensory processing. Many individuals on the autism spectrum excel in detail-oriented tasks, pattern recognition, and systematic thinking, helping them excel at data analysis, quality assurance, or IT.

Their ability to focus deeply on specific interests can lead to innovative solutions and thorough problem-solving approaches.

ADHD is characterized by challenges with attention regulation, impulsivity, and hyperactivity. However, individuals with ADHD are often highly creative and able to think outside the box. Their adaptability and quick idea generation can make them exceptional in fast-paced roles, such as marketing or project management, where quick thinking and innovative approaches are essential.

Dyslexia is a neurological condition that primarily affects reading and language processing, which can impact tasks involving reading and written communication. However, many individuals with dyslexia have strong visual-spatial skills and problem-solving abilities, excelling in roles that require strategic thinking and creative visualization, such as design, engineering, or entrepreneurship.

Learn how fostering a neurodiverse workplace can transform your culture and boost your organization's potential.

Benefits of neurodiversity in the workplace

It’s no secret that some of the most successful business leaders have dyslexia, dyscalculia, or ADHD, including Richard Branson, Charles Schwab and Carol Greider, a Nobel-winning molecular biologist. And many large employers, including Goldman Sachs, IBM, JPMorgan Chase, and Microsoft, have already launched programs to hire and advance neurodiverse talent.

The innovative capabilities that neurodiverse people bring are many and varied. Autistic people sometimes have extraordinary powers of pattern recognition, some people with ADHD have an unusual ability to maintain deep focus and great stores of energy, and many dyslexic people have superior spatial reasoning and visual imagination.

1. Creativity and innovation

Neurodiverse employees have varied cognitive approaches that enable them to solve problems in unconventional ways, leading to fresh ideas and solutions. By harnessing this creative thinking, organizations can enhance their competitive edge and foster a culture of continuous improvement and exploration.

2. Better information processing

Neurodiverse employees often have distinct strengths in information processing, helping them analyze data and identify patterns quickly and effectively. Their varied cognitive styles and heightened attention to detail can help them recognize nuances that others might overlook. These strong processing capabilities enable them to synthesize complex information quickly, making them adept at problem-solving and decision-making.

3. A broader talent pool

Hiring neurodiverse employees broadens the talent pool by tapping into a diverse range of skills and perspectives that are often overlooked in traditional recruitment practices. This enables organizations to access the unique talents of neurodiverse people. This not only enhances team dynamics but also fosters a culture of innovation and adaptability.

4. Enhanced company culture

Hiring neurodiverse workers can foster empathy and understanding among team members, creating a more supportive and collaborative atmosphere. As neurodiverse individuals contribute unique insights and innovative ideas, the overall creativity and problem-solving capacity of the team improves.

This can help cultivate a culture of respect and acceptance, making the organization more attractive to top talent and resulting in increased employee engagement.

Challenges of a neurodiverse workforce

Members of the neurodivergent community often face difficulties with communication and social interactions, which can lead to misunderstandings or feelings of isolation in team settings. Sensory sensitivities may also create discomfort in traditional office environments, making it more difficult for them to concentrate and perform effectively.

Additionally, navigating organizational structures and expectations can be overwhelming, particularly if these systems do not account for diverse cognitive styles, potentially impacting job performance and satisfaction.

Let’s break down some of these challenges:

1. Communication and social interaction

Neurodiverse employees might struggle to interpret social cues and nuances that neurotypical colleagues may take for granted. This can lead to misunderstandings and difficulty in building relationships. Many neurodiverse individuals also prefer direct and clear communication, which can clash with the ambiguous styles common in many workplaces.

Managers can play a crucial role in supporting neurodiverse employees by fostering a more inclusive environment. This includes training all staff on neurodiversity, encouraging open communication, and actively promoting a culture of acceptance.

Managers can also establish regular check-ins to understand individual needs, offer clear guidelines for tasks, and facilitate social interactions in structured ways, such as team-building activities designed for varying comfort levels with social interactions.

2. Recruitment and retention challenges

Systemic barriers in hiring practices, such as reliance on traditional interview techniques and assessments, often disadvantage neurodivergent candidates who may struggle with conventional formats. Even job descriptions can contain limiting or casual ableist language that may deter a neurodivergent person from applying.

Retention challenges arise from a lack of support and understanding in the workplace, contributing to high turnover rates as neurodivergent employees may feel undervalued or overwhelmed by inflexible environments.

To improve retention, organizations can implement tailored onboarding processes, provide ongoing training for managers, and create supportive workplace accommodations that empower neurodivergent individuals to thrive.

3. Lack of accommodations and support

Leaders need to be aware that neurodivergent individuals may approach tasks differently than their neurotypical counterparts. To support neurodivergent individuals, companies can implement flexible scheduling, alternative communication methods, such as written instructions or visual aids, quiet workspaces, clear workflows, and regular feedback.

These accommodations can help enhance productivity and job satisfaction, fostering innovation and resilience within the workforce while benefiting the entire organization.

How do you make a workplace neurodivergent friendly?

Supporting neurodivergent workers’ careers isn’t about trying to neutralize their differences, according to Lyckowski. “We’re not broken,” she says. “It’s a matter of looking at strengths and at the environment and asking ‘How can I help you succeed?’ not ‘What accommodation do you need?’”

For example, some neurodivergent people are more productive and happier if they simply wear noise-canceling headphones in the office or work under dimmed lights. “We’re looking to create situations where particular neurodiverse people can flourish with their technical abilities,” says Brush.

Splunk has found that some autistic people excel at the very complex analytical work required in cybersecurity, where millions of job openings go unfilled.

Brush finds that some neurodivergent people, having grown up in online communities, are more comfortable interacting with peers via social channels such as those in Microsoft Teams and Slack.

Your company may want to partner with a knowledgeable government agency or nonprofit organization to learn how to better serve neurodiverse job candidates and employees. Neurodiversity HubOpens in a new tab offers a directory of helpful resources for employers.

Implement flexible work arrangements

Flexible work arrangements can significantly enhance productivity and well-being for many neurodivergent employees. By allowing options such as remote work, flexible hours, and customized workspaces, employers can more aptly accommodate diverse sensory and cognitive needs.

For instance, neurodiverse individuals might thrive at home, in quieter settings, or may require specific tools to help manage their focus, underlining the importance of remote work diversity and inclusion.

Promote open communication

Encouraging transparent dialogue helps to break down barriers and allows neurodiverse individuals to express their needs, preferences, and challenges without fear of judgment. Employers can facilitate better communication by providing various channels, such as one-on-one meetings, anonymous feedback options, and open forum meetings, which can cater to different comfort levels.

Additionally, training all employees on inclusive language in the workplace can help create a healthier work environment where employees feel more psychologically safe.

Explore effective strategies to nurture a culture of continuous feedback, promoting collaboration and improvement.

Provide neurodiversity training and resources

Training sessions can educate employees about neurodiversity, helping to dispel myths and foster understanding between team members. This knowledge equips employees to interact more effectively and empathetically with their neurodiverse colleagues. Additionally, offering resources such as toolkits, guides, and access to mentorship programs can empower neurodiverse individuals to thrive in their roles.

Looking for more impactful ways to train your employees in DEI? We made a customized guide just for you.

Establish Employee Resource Groups (ERGs)

Employee Resource Groups (ERGs) play a vital role in fostering a supportive and equitable workplace. This includes not only considerations of race, gender, and culture but also supporting neurodiversity in the workplace, recognizing and respecting different cognitive styles and needs.

These groups provide a safe space for neurodiverse individuals to connect, share experiences, and discuss challenges unique to their work lives. They also create space for networking and collaboration, allowing neurodiverse employees to build relationships and advocate for their needs.

Additionally, these groups can serve as a valuable resource for managers, offering insights into practices and policies that can enhance inclusivity. Ultimately, ERGs not only empower neurodiverse employees but also contribute to a culture of understanding and acceptance, benefiting the entire organization by facilitating diversity and inclusion in the workplace.

Want to more deeply understand the importance of ERGs?

Tailor management methods

By recognizing the diverse cognitive styles and needs within this group, managers can adapt their leadership approaches to better serve these employees. Offering clear, structured instructions, providing flexible deadlines, and allowing for alternative communication methods can all be extremely helpful.

Providing personalized feedback and regular check-ins can also help create a supportive environment where neurodiverse employees feel valued and understood.

Use nontraditional assessment and training processes

Instead of relying solely on conventional testing or training methods, companies can implement hands-on, experiential learning opportunities that allow neurodiverse individuals to demonstrate their extraordinary skills in practical settings. Additionally, using a variety of assessment formats, such as project-based evaluations, can provide a more accurate picture of an employee’s capabilities.

Once we’ve hired neurodiverse people, are we done?

As with all employees, neurodivergent new hires aren’t likely to achieve their professional potential if, after onboarding, they’re left to sink or swim. That’s a key reason why IBM offers neurodiversity acceptance training to all employees in multiple countries and languages.

Supervisors should check in regularly with neurodiverse workers and keep them focused not only on the job at hand but also on their path forward in the organization. “Managers need to be more proactive in sponsoring talent they want to stay in the organization and grow in their careers,” says Brown.

For some neurodivergent professionals, this may mean charting a career path that doesn’t entail climbing a ladder to manage ever greater numbers of people. “I’ve tried to champion new, nontraditional managerial paths, like managing a technical lab,” says Brush.

FAQs

Why is it so important to hire neurodiverse employees?

Hiring neurodiverse employees is crucial because it brings in diverse perspectives and innovative problem-solvers who can enhance creativity and productivity within teams. Additionally, fostering an inclusive work environment not only supports social equity but also attracts a broader talent pool, driving organizational success.

What are the best ways to support neurodiverse employees in the office?

To support neurodiverse employees in the office, leaders should provide tailored accommodations, including flexible workspaces, sensory-friendly environments, and clear communication guidelines. Additionally, promoting awareness and training among all staff can help cultivate an inclusive culture that values diverse perspectives and fosters better collaboration.

Conclusion

Embracing neurodiversity in the workplace is not only important for diversity, equity, and inclusivity, but it’s also a powerful leadership initiative that can drive innovation and enhance team performance. By recognizing and honoring the unique strengths of neurodivergent employees and addressing the challenges they face, organizations can create more dynamic and supportive environments.

Neurodiversity inclusion also helps foster a culture of creativity and collaboration, which creates a ripple effect of positive benefits for the entire team.

About the author

Anna Picagli

As a CYT500 yoga instructor and a certified reiki practitioner, Anna is an advocate for holistic wellness, especially within the workplace.

She’s extremely passionate about the brain-body connection and exploring how mental and physical wellness intersect.

Anna has experienced firsthand how chronic stress, overworking, poor management, and other organizational issues can lead to extreme burnout. Knowing the impact that a toxic work environment can have on a person’s body, psyche, and general sense of well-being, she now works to direct others away from facing the same fate.

As Workhuman’s Content Marketing Senior Specialist, Anna is a regular contributor to Workhuman iQ reports and aims to create resources that company leaders can reference to help improve their culture and empower their employees, creating healthier workplaces for everyone.

In her free time, she’s a voracious reader and a seasoned home chef. You can learn more about Anna’s work on LinkedIn or through the Yoga Alliance.