Data Snapshot: Recognition and Employee Performance – Which Comes First?

2 min read

Clients frequently ask us about the relationship between recognition and performance, often measured as a subjective rating. We’ve done several studies using client data that show a positive correlation – the frequency and total value of recognition both relate positively to higher performance ratings. Still, the question of causality arises: Does recognition help drive better performance, or do higher performers simply receive more recognition?

To answer this question, we collaborated with a technology organization based in Ireland with about 2,500 employees globally. Within this organization’s peer-to-peer recognition program, employees can both give and receive for behaviors that demonstrate a core value, reflect a key strategic initiative, or focus on customers. This organization also runs performance reviews on a quarterly cycle, with high performers defined as in the top two of a six-point scale.

We analyzed this customer’s data over a 12-month span, giving us a rare longitudinal view into the relationship between recognition and performance. Here are the specific questions we sought to answer:

- Does a person’s current performance solely depend on past performance (suggesting any recognition is because of existing levels of performance)?

- Or does recognition reinforce and encourage behavior in a way that leads to greater performance above and beyond an individual’s existing performance?

Here's what we found

Several important findings emerged from the analysis that offer insight into the relationship between recognition and performance:

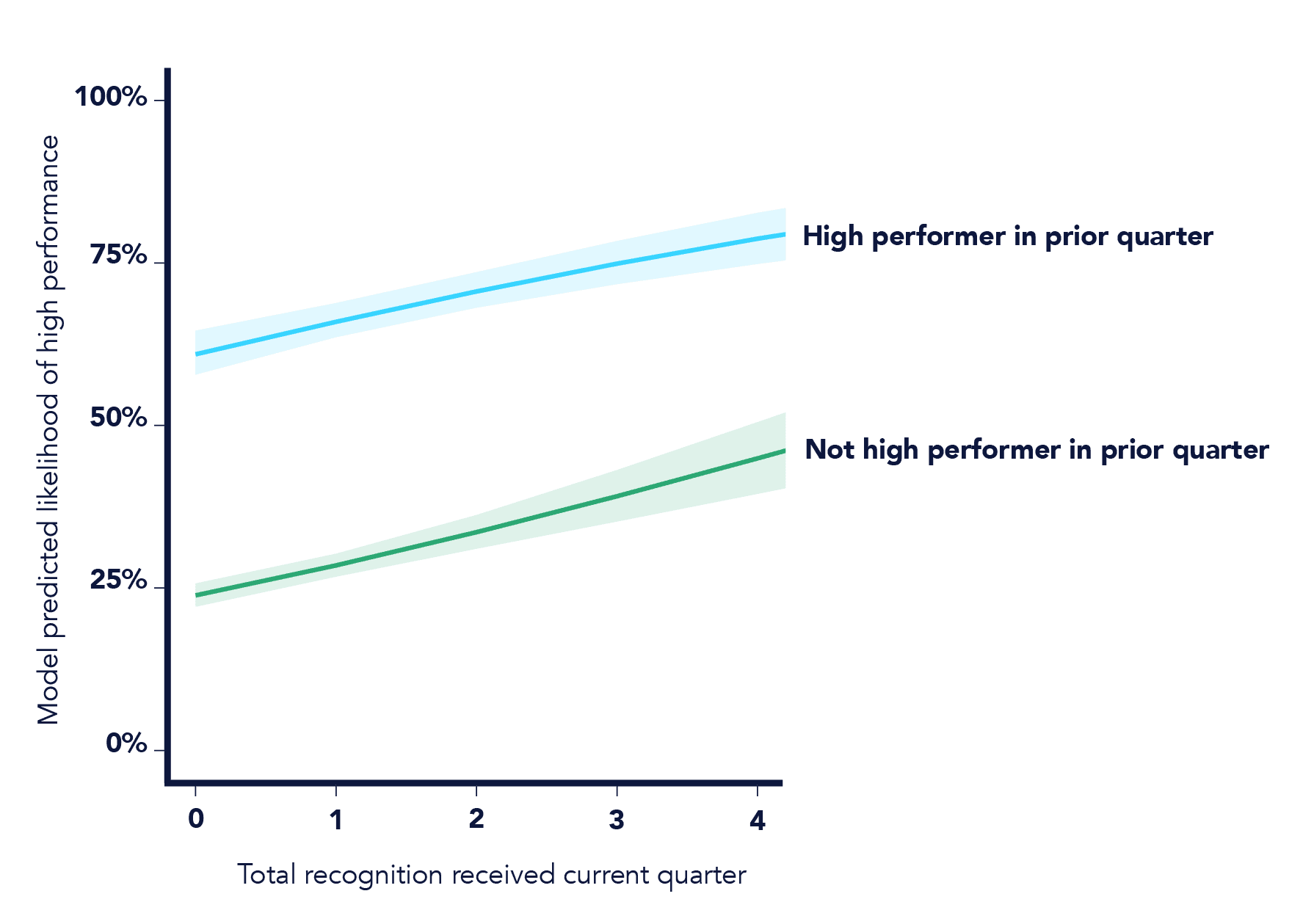

Each moment of recognition contributes to a greater likelihood of high performance, and that holds true whether the employee was previously a high performer or not – high performers are simply starting from a higher base probability.

These findings are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Illustration of model results, averaged over quarters, finding significant relationships between both prior performance and total recognition received on current performance

First, performance from the prior quarter was positively and significantly related to performance in the subsequent quarter.

If you were a high performer last quarter, you are more likely to be a high performer this quarter as well. This is represented in the visual as the vertical distance between the lines for previously high performers (blue) and everyone else (green). This is good news for the validity of the performance review system.

Second, controlling for prior performance, the amount of recognition an employee receives is significantly and positively related to performance in that quarter.

In other words, the frequency of recognition received increases the likelihood of receiving that high-performer designation (shown in the visual as the positive slope on both lines). This suggests that a part of improving performance is the type of positive reinforcement and learning that occurs when employees receive recognition in a well-designed programme.

Finally, there was not a significant interaction between prior performance and recognition.

In more plain language, while there’s a difference in the

base likelihood of improving performance based on past performance, the ability of recognition to reinforce positive performance behaviour is equally effective across consistent and high performers. In the visual, the lines run parallel for both groups rather than converging or diverging as more recognition is accrued.

What this means

In this study, we found a significant and positive relationship between recognition and performance, while controlling for prior performance over multiple time frames. The robustness of the modeling approach and findings suggests a role for recognition as a strategic tool in improving organisational performance, by ‘catching’ and reinforcing behaviours that lead to greater productivity, service or effectiveness.

As with any study not using true experimental methods, causality is difficult to fully determine. However, the more data are observed to support a relationship, the greater our confidence can be that recognition supports some part of improved performance. This information, combined with the practical need for cost effectiveness, should encourage organisations to seriously evaluate the important role that recognition provides in a performance improvement context.

Methodology

Data were aggregated by person-quarter, so each individual had up to four time periods in the data set. Recognition was measured as the frequency (count) of recognition received during each of the quarters. Performance was also measured quarterly as a binary variable: 1 if the individual was a high performer or 0 if otherwise. Lagged performance was captured as the individual’s performance rating from the prior quarter.

Model results

Given the longitudinal, nested nature of the data, we ran a generalised linear mixed model (GLMM), regressing as fixed effects lagged performance, total recognition received and time on current quarter’s performance, with individual as a random effect (data are clustered by person). Model estimates for fixed effects are shown in Figure 2.

For ease of presenting Figure 1, the results are illustrated via the estimated marginal means for recognition frequency and lagged performance rating (i.e., predictions are averaged over quarter). Model syntax and summaries are available upon request.

Figure 2. Model estimates for fixed effects

| Predictor | B (SE) | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -0.56 (0.124) | -4.48 | <0.001 |

| Total recognition received | 0.24 (0.033) | 7.32 | <0.001 |

| Prior performance | 1.61 (0.087) | 18.39 | <0.001 |

| Quarter (time) | -0.07 (0.013) | -5.12 | <0.001 |

| Interaction: rec. & perf. | -0.02 (0.048) | -0.49 | 0.627 |