Functional Organizational Structure: Examples, Fit Assessment, Model Comparisons, and Implementation

Table of contents

- What is a functional organizational structure?

- Advantages of a functional organizational structure

- Disadvantages and common challenges

- When to use a functional organizational structure

- Functional vs. divisional vs. matrix: key comparisons

- Functional structure in specific industries and contexts

- Real-world examples: companies using functional structures

- How to transition to a functional organizational structure?

- How to create and implement a functional organizational chart

- Leadership roles in a functional structure

- FAQs

- Conclusion

A functional organizational structure groups employees by specialized roles — marketing, finance, HR, operations — under dedicated department heads. It's one of the oldest and most common frameworks, offering deep specialization and clear career paths. But it also introduces coordination challenges as companies scale.

You're likely here because you're weighing whether this model fits your organization, or you're preparing to implement or transition away from one. Maybe you're seeing silos form between departments, or you're wondering if a functional setup can support your growth plans.

This guide explains what a functional structure is, how it compares to divisional and matrix models, its trade-offs, and when human resources leaders should recommend it. You'll get assessment frameworks, implementation steps, real-world examples, and side-by-side comparisons to help you make an informed choice.

You'll get assessment frameworks, implementation steps, real-world examples, and side-by-side comparisons to help you make an informed choice.

By the end, you'll know whether a functional organization structure aligns with your company's stage, industry, and strategic priorities — and how to build or evolve one that works.

Key Takeaways:

- A functional organizational structure groups employees by specialty (e.g., finance, marketing, operations), with centralized decision-making and clear reporting lines.

- Functional structures can improve efficiency and quality by reducing duplicated work and standardizing processes within each function.

- They also support clearer career paths and skill depth through function-based progression, mentorship, and training opportunities.

- The biggest trade-offs are silos, slower cross-functional coordination, and bottlenecks as decisions move up and down the hierarchy.

- Functional models tend to fit best for single-product focus, regulated/specialized work, or organizations prioritizing consistency and process control—and often need hybrid elements as complexity grows.

- If you’re unsure about fit, use an assessment framework (and even a simple decision matrix) to evaluate product complexity, growth plans, and where accountability breaks down today.

- Successful transitions require more than an org chart: define functional scope, document decision rights, confirm leaders, communicate early, and set cross-functional operating rhythms (e.g., shared OKRs, reviews).

What is a functional organizational structure?

A functional organizational structure is a hierarchical model that groups employees into different departments based on specialized functions, such as marketing, engineering, finance, HR, and operations. People work alongside others who share similar expertise and responsibilities, and each department is typically led by a functional manager who reports to a central executive, such as the CEO or a member of the C-suite.

Because the structure is vertical and top-down, reporting lines are clear, and decision-making often flows through functional leaders. This setup supports deep skill development within each function, standardized processes, and consistent ways of working across the organization.

Functional hierarchical structures are common in organizations with stable, repeatable processes and in larger companies where specialization improves efficiency. They are also frequent in early-stage companies that need clear ownership of core capabilities before they expand into multiple products, regions, or business units.

Core characteristics

Most functional organizations share these traits:

- Employees grouped by similar job functions and areas of expertise

- Centralized decision-making through functional leaders

- Clear reporting lines, defined roles, and layered management

- Shared resources and budgets managed by department heads

- Functional career paths with clear progression within a specialty

- Clear accountability within each function due to defined ownership

History and evolution of the functional model

The functional model is closely tied to scientific management, which emphasized specialization and efficiency in the early 20th century. It became especially useful in industrial and corporate settings where standardization and scale mattered.

As knowledge work expanded and product complexity increased, many organizations introduced product-focused, divisional, or matrix elements to improve speed and cross-functional coordination.

At the turn of the 20th century, Frederick Taylor applied the lessons he learned working in a steel mill to management structures more broadly. He saw that workers on the floor understood their trade much better than their bosses and wanted to build a system that could incorporate that knowledge.

Taylor's ideas quickly gained traction in the booming industries of the early 20th century. It helped companies such as Ford and General Motors improve standardized processes and perform manufacturing at an enormous scale. Functional models dominated workplaces through the 1980s, especially at larger and more stable businesses.

How a functional structure works

In a functional organizational structure, work is organized into functional departments, each responsible for a specific set of activities (for example, finance manages budgeting, marketing manages demand generation, and operations manages delivery).

Functional leaders set priorities, standards, and processes within their teams, while the upper management coordinates across departments to ensure the functions stay aligned to overall business goals.

Advantages of a functional organizational structure

A functional organizational structure can benefit both employers and employees, especially when the organization values consistency, efficiency, and deep expertise.

Efficiency and expertise

Because teams are grouped by specialty, functional structures can create economies of scale within each department and make it easier to build repeatable ways of working. Common advantages include:

- Reduced duplication of roles, tools, and vendors within the function

- More consistent, standardized processes and quality control

- Concentrated knowledge of best practices inside each department

- Faster onboarding and training when hiring for clearly defined specialties

- High focus on a narrow set of responsibilities, which can improve speed and accuracy over time

Career development

Functional structures often make growth paths more visible because roles and expectations are defined within each specialty. That can support:

- Clear career progression within a function (for example, analyst → senior analyst → manager)

- Mentorship and coaching from senior specialists in the same discipline

- Skill-building opportunities that prioritize depth, not breadth

- Access to function-specific certifications, credentials, and training programs

- Clearer performance standards because success is measured against established functional outcomes and competencies

Disadvantages and common challenges

A functional organizational structure can be effective, but it also introduces trade-offs, especially when work depends on coordination across departments.

Silo effect

When teams are organized primarily by specialty, it’s easier for departments to optimize for functional goals instead of shared business outcomes. Common challenges include:

- Teams prioritizing functional metrics over end-to-end results

- Slower information flow across departments due to handoffs and approvals

- Confusion about ownership when cross-functional work stalls

- Increased risk of finger-pointing when deliverables require multiple functions

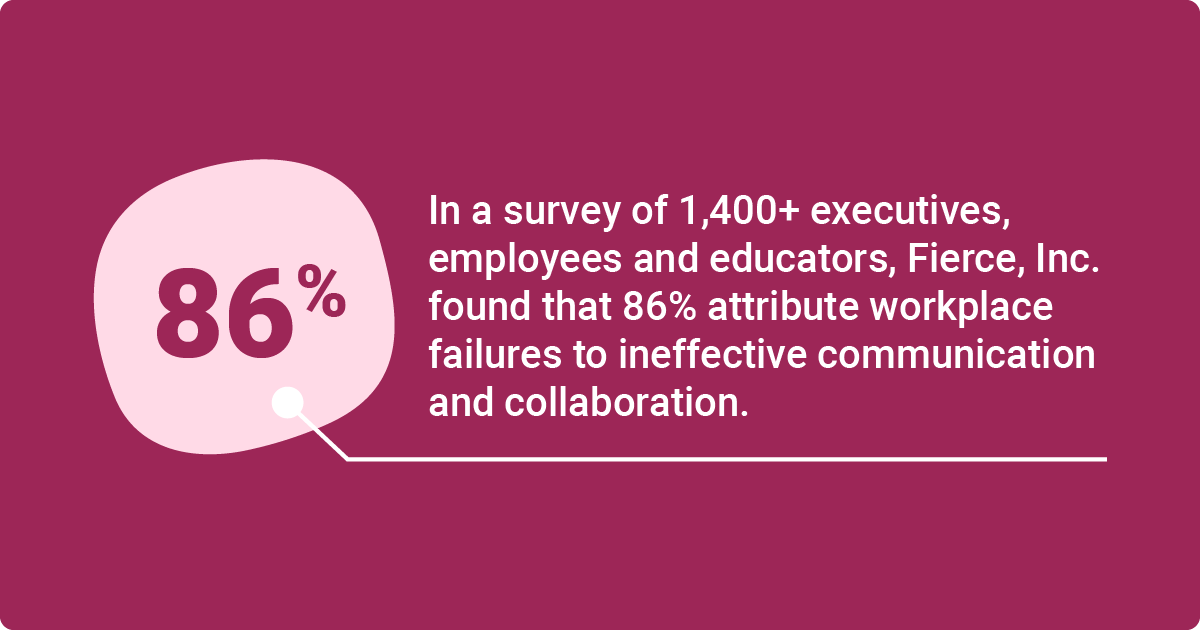

Communication breakdowns can compound these issues. According to a Fierce, Inc. press release summarizing a survey of more than 1,400 corporate executives, employees, and educators, 86% of respondents attributed workplace failures to a lack of collaboration or ineffective communication.

Breaking down silos usually requires clear operating rhythms (shared goals, decision rights, and cross-functional forums), not just good intentions. In practice, it also helps to reduce workflow friction.

For example, Workhuman® Cloud Integrations connect with tools many teams already use — such as Slack, Microsoft Teams, and Workday — so recognition and communication can happen within existing workflows, improving cross-department visibility without adding yet another system to manage.

Building on Workhuman’s initial Teams integration, the new app – available for download in the MS Teams app storeOpens in a new tab – embeds your organization’s recognition program directly into the Teams environment where your employees are already working, meeting, and collaborating every day.

Scalability limits

Functional structures tend to work smoothly in smaller or more focused organizations, but coordination costs usually rise as headcount, locations, or product lines grow. As complexity increases, organizations may experience:

- Slower responsiveness to market changes because decisions move up and down the hierarchy

- Bottlenecks that limit how quickly ideas and feedback travel upward

- A bias toward optimizing existing processes over experimenting with new approaches

For highly diversified, multi-product, or multi-region companies, a functional structure often works best as part of a hybrid — paired with divisional units, cross-functional roles, or a matrix layer to improve speed and accountability.

When to use a functional organizational structure

So, when does it make sense to use functional structures?

Ideal use cases

Many start-ups and new organizations employ a functional organizational structure. It offers a clear structure of command amid the chaos of a new business and allows departments to develop good procedures for functional work.

Many larger and more established organizations in stable industries also use functional structures, especially when they want to prioritize efficiency and process control. Walmart, for instance, has increased supply chain efficiency and ensured the implementation of executive ideas with the help of a functional organizational structure. This functional approach also allows employees plenty of opportunities to rise into management.

Industries subject to heavy regulation or that require deep specialized knowledge, such as pharmaceuticals, finance, and engineering, can also benefit. Though BMW uses regional and product-based groupings, its corporate structure is still functionally organized. This helps maintain tight managerial control in departments like finance and development, where deep knowledge and clear accountability are key.

When to avoid or evolve

Organizations that have a diverse product offering or require quick and nimble decision-making may be better off avoiding a functional organizational structure. For instance, the functional structure of the Dyson company may have been an impediment when the company unsuccessfully tried to diversify into electric cars.

Companies that are growing quickly or expanding into new areas may need more agility and cross-functional speed than a functional structure can provide.

So do companies with multiple business units, especially if those units require distinct strategies or serve different customers. Microsoft introduced a division-based, flat structure in 2014 after Satya Nadella took the CEO job, and the move away from a functional structure has helped the company improve AI innovation.

Customer-centric strategies often require end-to-end ownership of decision-making and faster implementation of changes. For instance, Toyota decentralized its organizational structure in part to address its slow response times to safety issues.

Assessment framework: Is a functional structure right for you?

These questions will help you determine if a functional structure is right for your organization.

- Do you offer one core product or service, or do you have multiple product lines?

- Are you in a stable industry and market, or is the competitive and regulatory environment changing quickly?

- In terms of both geographic spread and workforce, how much do you plan to expand in the next few years?

- Does your organization require more specialized knowledge or cross-functional capability?

- Does your organization already struggle with unclear ownership and slow decision-making?

Consider using a decision matrix, where you rate your organization on five to seven key dimensions to determine if a functional framework is right for you. Because org design is a long-term choice, aligning the outcome to strategic planning models can help ensure the structure supports your bigger business goals.

Functional vs. divisional vs. matrix: key comparisons

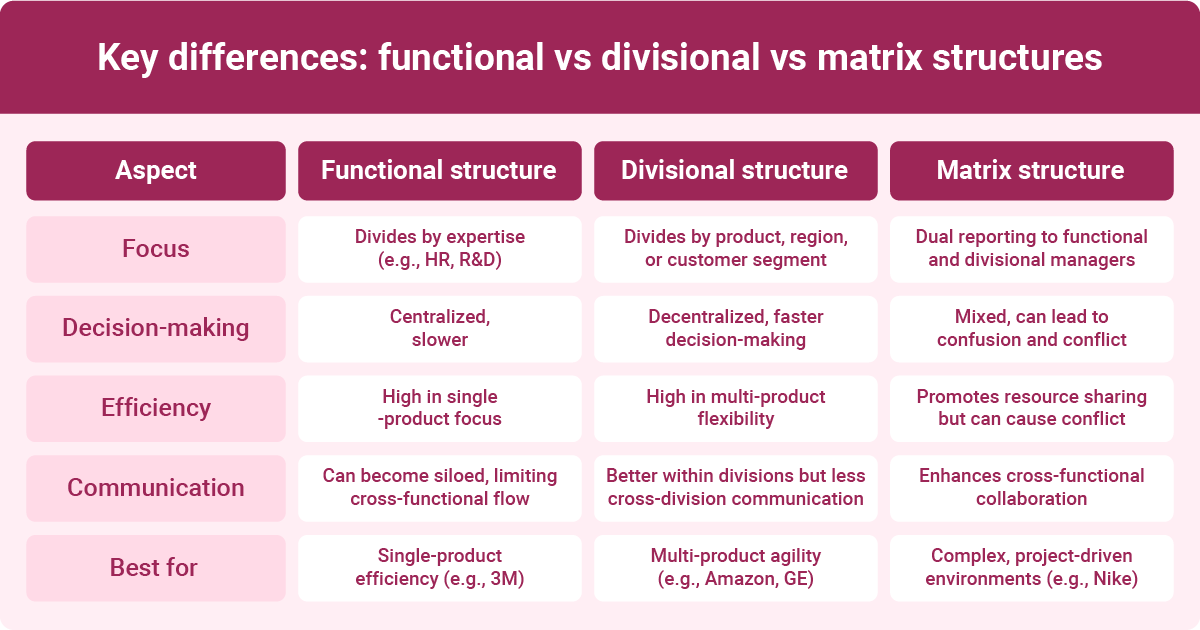

While a functional structure divides employees by expertise, a divisional structure divides employees by product, region, or customer segment. In a matrix system, employees report to both a functional manager and a divisional manager.

Functional vs. divisional structure

A functional structure is centralized and expertise-focused, excelling in efficiency. However, there's a risk of departments becoming siloed and causing a breakdown in cross-functional communication. It may also take longer for decisions to get implemented.

Functional and divisional structures differ in their foundation. A divisional organizational structure is decentralized and customer-focused. Units are empowered to work more independently, which leads to faster decision-making, but also risks duplicating work.

Functional structures work best for single-product efficiency, whereas divisional structures work best if you need multi-product agility. 3M uses a functional structure to leverage its deep R&D expertise, while Amazon and GE both use a divisional organizational structure to service multiple different products.

Functional vs. matrix structure

A matrix organizational structure layers project or product reporting lines on top of functional departments. While this improves cross-functional collaboration and facilitates a more efficient share of resources, it can also create dual reporting relationships, confusion, and increased conflict.

A functional structure is relatively easy to manage, but a matrix structure requires a strong culture of accountability and conflict resolution. However, matrix structures work well in complex, project-driven organizations such as consulting or aerospace. Nike also uses a matrix structure.

Functional structure in specific industries and contexts

According to the article 'Understanding Healthcare Organizational StructuresOpens in a new tab' by Functionly, many hospitals and healthcare organizations adopt functional structures. Clinical departments such as radiology, neurology, and surgery are used alongside support departments such as IT or billing.

Manufacturers also use functional structures. Quality control, logistics, facilities, and operations are organized as distinct departments.

Professional services find functional structures useful. A finance company will likely have separate departments for tax, litigation, and audit, for instance.

Government organizations and public institutions are another example. Mission-based departments such as fundraising or community outreach are supported by IT, finance, and HR departments.

Even project management contexts employ functional structures, where functional managers retain authority over resources, even when employees are assigned to cross-functional teams. This differs in divisional and matrix structures.

Real-world examples: companies using functional structures

You'll find functional structures in small, medium, and large companies, especially in those that are new.

Startup example

Let's take a look at a 50-person startup Software-as-a-Service, or SaaS, company. The C-Suite is a CEO assisted by vice presidents of engineering, sales, marketing, and customer success. Each of those VPs heads up a department of 10 to 12 employees. Decisions are centralized and channeled through VPs.

This functional structure helps the company keep a clear chain of command and establish accountability. Centralizing decisions makes sure everyone is on the same page, and no one is improvising. While the company is building a single product with clear functional needs, a bit of hierarchy makes sense.

A research titled ‘The myth of the flat start-up: Reconsidering the organizational structure of start-ups’ has shown that a hierarchical organizational structure is positively correlated with commercial success for startups.

Established company example

Let's look at a regional bank. Even though there may be a dozen or more branches, it doesn't make sense for each to function as its own fully independent unit, so the bank runs functional departments for IT, finance, HR, and compliance. Individual bank managers have access to support from these departments while maintaining some control over decisions at their branch.

How to transition to a functional organizational structure?

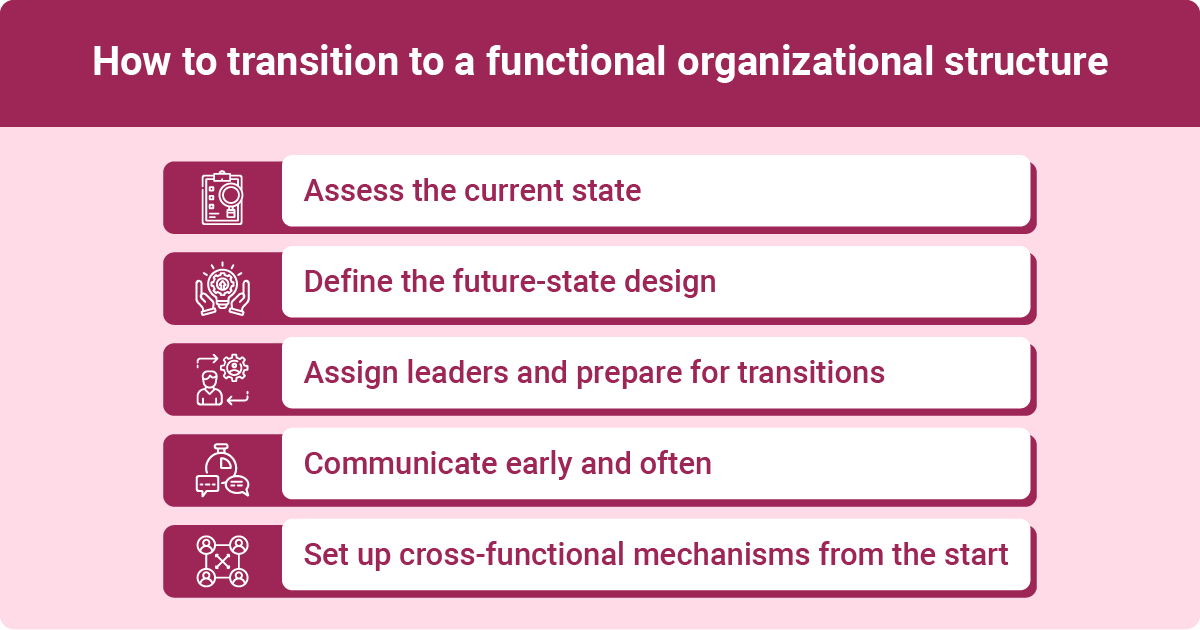

Moving to a functional organizational structure is a significant change, so plan for a staged rollout rather than a quick reorg. Start by documenting your current operating model, then design the future state with clear roles, decision rights, and cross-functional ways of working.

- Assess the current state

- Map your existing org chart and reporting lines.

- Identify your functional domains (for example, finance, marketing, operations, HR, engineering).

- Clarify where work and accountability currently break down, especially across teams.

- Define the future-state design

- Establish scope boundaries for each function, including what each team owns and what it supports.

- Document decision rights (who decides, who advises, who executes) and escalation paths.

- Identify cross-functional work that will require shared governance from day one.

- Assign leaders and prepare for transitions

- Confirm functional leaders and clarify expectations for their roles.

- Plan leadership handoffs, including how priorities, budgets, and performance metrics will move.

- Equip managers with the tools and training they need to lead through change. Reorgs can shift decision rights and reporting lines quickly, so guidance on managing leadership transitions can help leaders plan handoffs and keep teams steady.

- Communicate early and often

- Explain the rationale, timeline, and what will change for employees.

- Address career-path questions and concerns about collaboration across functions.

- Pilot the model with one function or business area first, then expand based on what you learn.

- Set up cross-functional mechanisms from the start

- Create operating rhythms such as steering committees, shared OKRs, and regular cross-functional reviews.

- Standardize intake, prioritization, and handoff processes so work does not stall between departments.

- Establish visibility into progress so dependencies and bottlenecks are surfaced quickly.

During transitions, it helps to reinforce alignment and coordination across the organization. For example, keeping communication and recognition consistent across teams, including in the tools employees already use, can support engagement and cross-functional visibility while reporting structures change.

Common pitfalls and change management tips

Functional transitions often fail because the org chart changes, but the operating system does not. Avoid these common mistakes:

- Underestimating how new reporting lines affect power dynamics, decision-making habits, and working relationships

- Announcing the structure without clarifying decision rights, escalation paths, and cross-functional protocols

- Misaligning performance expectations and incentives with the new functional responsibilities

- Neglecting cross-functional governance (for example, steering committees, intake processes, and shared metrics)

- Rolling out changes all at once instead of piloting and iterating

To build confidence, involve functional leaders and key stakeholders early, pressure-test the design with real workflows, and plan for resistance. Clear messaging, manager enablement, and steady reinforcement of the new ways of working will make the change stick.

How to create and implement a functional organizational chart

Once you’ve decided a functional structure is the right fit, your organizational structure outline becomes the source of truth for reporting lines, functional ownership, and how work should flow. The goal isn’t just to draw boxes; it’s to document the structure clearly, make it usable day to day, and keep it current as the business evolves.

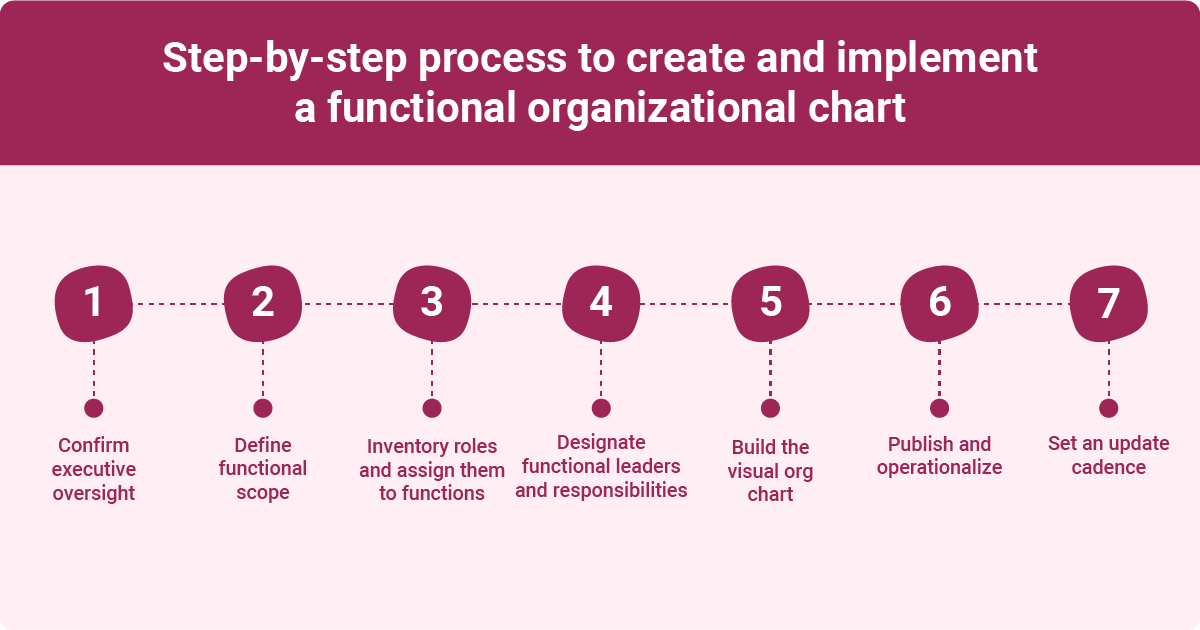

Step-by-step process

Use these steps to build and roll out a functional org chart:

- Confirm executive oversight

- Define the executive roles that oversee functions (CEO/C-suite) and which functional leaders report to them.

- Define functional scope

- Clarify what each function owns vs. supports, including where handoffs happen between departments.

- Inventory roles and assign them to functions

- List all roles and map each one to a primary function.

- Note shared-service support where relevant (for example, HRBP support across business areas).

- Designate functional leaders and responsibilities

- Identify functional leaders and document what they are accountable for, including budgets, priorities, and standards.

- Build the visual org chart

- Create a clean, readable chart with clear reporting lines, management layers, and consistent naming conventions.

- Publish and operationalize

- Share the chart in a centralized location that employees can easily access.

- Pair it with a short “how to use this chart” guide that clarifies decision rights and escalation paths for cross-functional work.

- Set an update cadence

- Schedule periodic reviews (quarterly, or after major org changes) to keep the chart accurate as roles and priorities shift.

Tools and templates

A functional org structure is easier to adopt when teams have a small toolkit they can use immediately. Consider providing:

- An editable org chart template in PowerPoint or Google Slides

- Org chart software or diagramming tools to maintain a single current version

- A RACI matrix template for cross-functional work (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed)

- Checklists and step-by-step guides for department managers (onboarding, handoffs, approvals)

- An assessment questionnaire leaders can use to confirm fit and flag gaps

- A review schedule and ownership model so updates are consistent and timely

This keeps the chart from becoming a one-time exercise—and turns it into a practical reference teams can rely on as the organization grows.

Leadership roles in a functional structure

Leaders in a functional organization operate within a clear structure, but they need to work together to avoid silo behavior.

CEO and executive team

In a functional structure, a CEO sets the strategy, integrates information across the company's functions, and resolves cross-functional conflicts, while functional directors own the expertise, budget, and headcount for their departments.

Because of the risk of siloing and communication breakdown, the executive team should meet regularly to align priorities and ensure they understand the CEO's customer and market strategy.

A functional structure puts a lot of pressure on functional department heads. They need to have deep functional knowledge, as well as leadership abilities.

Functional managers

Functional managers operate underneath department heads and are more responsible for day-to-day responsibilities. They oversee teams within a broader function and need both deep function knowledge and management and coaching skills.

Functional managers are responsible for day-to-day execution, including workload planning and quality within their teams. They're also key in coaching, performance management, and skills development.

They often manage budgets, tools, and other resources for their teams, though they do not take accountability the way department heads do. Their performance is evaluated against functional key performance indicators (KPIs), such as campaign performance, that align with the company's strategic goals.

Department heads and functional managers: roles and responsibilities

Department heads and functional managers work together to run the function effectively. They shape the function’s strategy in line with enterprise priorities, while also overseeing budget and resource allocation, headcount planning, and staffing needs.

They also set the function’s standards—processes, best practices, and quality benchmarks—and build a sustainable talent pipeline through hiring, training, and promotion decisions.

In cross-functional work, they represent their function’s perspective while helping teams stay aligned on shared outcomes, balancing functional excellence with the flexibility required to deliver end-to-end results.

To strengthen talent decisions inside a function, analytics can add visibility beyond what leaders can observe day to day. For example, Workhuman® iQ™ can help functional leaders spot skills patterns, identify mentorship opportunities, and understand team engagement signals by analyzing recognition data—supporting stronger development plans and more confident succession planning for leaders.

"What gets measured gets managed." But how do you get an accurate measure of skills? Don't rely on resumes or one-off evaluations.

With Workhuman iQ® you can easily understand skills across your organization. The tool uses proprietary algorithms and NLP to identify skills in peer recognition messages and classify them in an easy-to-read distribution chart for an team or company.

Harness the combined powers of AI and recognition—Human Intelligence™—to crowdsource authentic, sustainable skills insights.

Employee experience and career development in functional structures

A functional structure can create a strong employee experience when people want role clarity and the chance to build deep expertise. Clear responsibilities, consistent performance expectations, and well-defined processes can make it easier for employees to understand what success looks like and how their work contributes to their function.

The trade-off is breadth. Employees may have limited exposure to other parts of the business, which can narrow their perspective and slow collaboration if cross-functional relationships are not intentionally built. Over time, employees can become more siloed in their specialty unless leaders create pathways for broader learning.

Functional structures can also shape who gets promoted. Because technical excellence is highly visible within a function, top performers are often moved into people leadership roles. The risk is that strong individual contributors may not yet have the coaching and leadership skills needed to thrive as managers.

Gallup has noted, in their article, ‘When Good Frontline Workers Make Bad SupervisorsOpens in a new tab’, that frontline supervisors promoted based on individual performance are less engaged than those selected for supervisory skills or prior supervisory experience, which can affect the teams they lead.

To keep the benefits while reducing the downsides, build development opportunities that intentionally expand networks and skills, such as:

- Job shadowing across functions

- Cross-functional project assignments with clear decision rights and ownership

- Short-term rotation programs for high-potential talent

- Manager readiness programs that develop coaching, feedback, and performance management skills before promotion

FAQs

What is a functional organizational structure?

A functional structure groups employees into departments based on their specialty and tasks. Each department is led by a functional manager who reports to the C-suite.

What are the main advantages of a functional structure?

A functional organization offers clear chains of command and paths for career advancement. It centralizes decisions and can help promote unified policies.

When should a company use a functional structure?

Functional structures are useful for start-ups or small companies, companies that focus primarily on one product or service, or companies that require deep specialized knowledge.

How do you create a functional organizational chart?

Start by outlining your current org chart, establishing new functional domains, and sorting employees by function. Then, clarify employee and manager roles before drawing up a new org chart and anticipating concerns.

Conclusion

A functional organizational structure can be a strong fit when your organization benefits from specialization, consistent processes, and clear accountability. By grouping employees into functional departments, you can build deeper expertise, reduce duplicated effort, and create more transparent career paths.

The trade-offs are real: silos can form, cross-functional work can slow down, and decision-making can become bottlenecked as the organization grows. The difference between a functional structure that works and one that frustrates people usually comes down to execution—clear decision rights, strong cross-functional operating rhythms, and intentional development programs that give employees visibility beyond their function.

If you’re considering a functional model, start with a clear definition of functional scope, pilot where possible, and build the governance and communication habits that keep teams aligned as complexity increases.

About the author

Ryan Stoltz

Ryan is a search marketing manager and content strategist at Workhuman where he writes on the next evolution of the workplace. Outside of the workplace, he's a diehard 49ers fan, comedy junkie, and has trouble avoiding sweets on a nightly basis.