How to Transform Today's DEI Practices: A Case Study with Workhuman & BLK Men in Tech

I want to take you back to October 2022. I’m in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, the sun is shining, and I’m attending the inaugural THRIVE Conference hosted by BLK Men in Tech.

Founded by Kham Ward, a diversity and inclusion executive with over a decade of experience, BLK Men in Tech (BMiT) is a non-profit that provides access, resources, and community for Black men within the tech industry and those interested in entering the space. And their THRIVE Conference is a four-day distillation of that mission.

The agenda is packed with insightful sessions and speakers. Recruiter Row connects attendees with top tech brands. The Resource Center provides resume and LinkedIn assistance and even gives visitors a new professional headshot. #Thrivekids is a day camp running in conjunction with the conference to help parents and guardians who need childcare support. They thought of everything.

And then there’s THRIVEFest, a celebration of music, dancing, and community to cap each day. THRIVE is described as an “unmatched” vibe. That is for a reason.

I’m here because there aren’t enough Black men in tech. (Or Black people in the workforce period.) And, as a researcher in the tech space and a Black woman, you could say I have a vested interest in changing that fact. To do that, I need to understand the full spectrum of the Black male experience in tech.

What better place to start than a conference with the exact same goal?

The survey

Our world craves quantitative data. Believe me, I get it. “Analytics” is in my job title. But sometimes the world can trick itself into thinking only if something can be measured, calculated, and spun into a clean number, can it be understood and valued. Qualitative data, on the other hand, introduces nuance, tells stories, makes you feel. That’s too messy.

The truth is both are important. And this survey, designed to understand the experience of Black men in tech, is so new as a concept that we needed qualitative data to properly build it. What good is a multiple-choice survey if none of those choices speak to your experience?

By interviewing attendees about their experience prior to creating our survey, we could make sure what we asked and how we asked it was as comprehensive and inclusive as possible.

The first step in this survey’s methodology was to build trust.

We talked about what these men have faced and what they’re currently going through. It was an intense and emotional experience. In our society, the stereotype of Black men is big, brawny, and dangerous. But those four days in Fort Lauderdale were marked by laughter, tears, vulnerability, and generosity.

The experience was also an incredible example of bravery. Kham often talks about the risk even taking a survey about their experience poses to Black men.

As soon as they enter a room, office, or white space, Black people are eyed, othered, and assessed. Seeds of distrust are sowed in an instant. Said one interviewee, “When you walk into a corporate environment, all of the preconceived stereotypes are already placed on you as a Black professional.”

From the jump, these Black men are walking on eggshells, trying with every word, every look, every outfit not to inadvertently offend or overstep and blow an opportunity that means everything to them, their family, and their community.

And now some HR company they’ve never heard of wants them to take a survey about how work could be better. Some have too much at stake to take that chance.

So, I would like to take this opportunity to thank our interviewees and survey respondents for taking a chance on us and helping us understand some of the urgent challenges they face at work.

The Challenges of Black men in tech

Our survey revealed four main challenges Black men in tech face at work: bringing their authentic selves to work, the effect of negative workplace experiences on their mental health, their broader financial responsibilities, and difficulties with career advancement.

The challenges are formidable. They run deep. But, as you’ll soon see, the solutions exist. We just need to implement them.

Bringing their authentic selves to work

At Workhuman, we often talk about the importance of psychological safety – the idea that you can bring your whole self to work. In a psychologically safe workplace, you can be who you are. There should be no need for codeswitching or wearing a metaphorical mask to hide your self-image. In theory.

Of our survey respondents, 89% felt that their race is an important part of their self-image. However, just 55% reported behaving at work in a way that reflects the “real them.”

In a psychologically safe workplace, employees should not fear making a mistake will be held against them. They should have the confidence to bring up tough issues and speak up with a suggestion or bold idea. Our interviewees repeatedly described the anxiety of saying the wrong thing or putting themselves in a vulnerable position.

Our interviewees talked about the hypersensitivity to how you show up at work. For one, that meant cutting dreads he had been growing for years because he was afraid of how it might affect his career. In a psychologically safe workplace, people can ask others for help and they certainly don’t feel like they need to change their appearance to be accepted.

“You must play the corporate game,” said one interviewee. “You have to find a way to disarm people to make them feel comfortable,” said another.

To be constantly conscious of how you are presenting yourself, to paint on a smile, stand on guard, and don the mask of “A-OK” is exhausting. And as we’ll see in the next section it has serious side effects.

Negative workplace experiences and the effect on mental health

In our presentation at Workhuman LiveOpens in a new tab, Kham provided some important context for our audience: Talking about mental health in the Black male community is not easy.

But we need to talk about it. About 75% of our survey respondents, and all our interviewees, reported having a negative experience at work due to their race and 36% of the survey reported their mental health suffered as a result of racial discrimination either in the past or to this day.

Those experiences led nearly half of respondents to say they feel mentally exhausted at the end of the day and 43% to say they often or always feel that way.

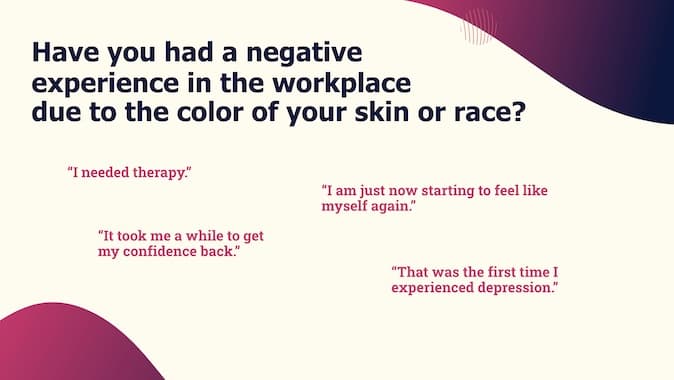

It’s difficult to express the depth of self-doubt you feel when that doubt is rooted in who you are. However, our interviewees could describe what that stress and doubt did to them.

They described panic attacks, psychogenic blackouts, experiencing depression for the first time, needing therapy for the first time, and a complete lack of confidence at work. In every case but one, the participants were either terminated or pushed out of the organization.

For many participants, these experiences occurred early in their careers, a point where they’re not fully aware of what can and can’t be done in the workplace. It was the start of their journey.

I couldn’t help but reflect on the fact that I was talking to those who made it through their first negative experience in tech. But what about all those people who didn’t make it past these experiences? How many more Black men in tech could we have talked to?

People like to say that they don’t care what other people think about them. And to some degree, that sentiment offers a relief from judgment. But your brain, your heart, and your soul light up when people think something positive about you.

Beyond the sheer pain, consistently negative experiences rob people of the emotional boon positivity offers and all of the redirections their lives can take when they receive it.

Broader financial responsibilities

Income and wealth inequality is higher in the United States than in almost any other developed country. It is an issue that stretches across race and ethnicity, but it is especially acute for Black people.

The average Black household earns about half as much as the average White household and they own about 15-20% as much net wealth. For many in the Black community, that can mean bearing the financial responsibilities for generations. When it's payday for you, it's, in part, payday for everybody.

In our survey, 84% of participants said they use their paycheck to support their immediate families, extended family, and communities. We had one interviewee reference a formal “others fund.” One described how he and his wife take time to dole out money as soon as it comes in.

The first role in tech for a Black man is so pivotal. So many men we interviewed nearly didn’t survive that experience. For those who didn’t grow up with professional examples, there are so many workplace etiquette things they don’t know.

Add to that a pressure to provide, to break the cycles of inequity, and with that pressure comes financial stress and distress.

For Kham, as well as many others, there are also the social and community implications to earning money. Especially when you’re earning more than those you grew up with. You can lose friends. You’re no longer just the kid from the block who went to school. Now you’re different and othered not just by those you work with but also by those you hope to turn to for support.

This leaves many in the Black community surrounded by pressure. When you take care of everyone else, who takes care of you?

Difficulties with career advancement

Moving up in your career, even reaching a leadership position requires so much to go right. The right situation, the right people, the right time. It also requires a sincere belief that you can achieve and advance.

For many participants, they described the lack of diversity in the company’s C-Suite as disheartening and discouraging. It made them feel their chances were slim to climb the corporate ladder.

Several participants questioned if they even wanted to be in the C-suite. Said one participant, “I’m not sure if I can. Hard work can only get you so far.” Forget the C-suite, another told us he had never been promoted in the 12 years he has worked.

This discouragement has downstream effects. Just 41% of our survey reported feeling highly engaged at work, 64% reported they’re looking for a new job in the next year, and only 32% strongly agreed that their unique skills and talents are valued and utilized.

Upward mobility can sometimes not even be a priority for Black men. If you have, as we referenced before, financial responsibilities outside of yourself or your nuclear family, are you going to stick it out at your current company for a title change that may never come or are you going to jump at a new opportunity that might set you behind on your career track but offers $30,000 more?

Besides, what chance would you give someone to be a leader if that person felt continually doubted because of who they are and what they look like? Someone who doesn’t feel they can trust those they work with or for. Someone who looks to the top of the org chart and isn’t likely to see someone who looks like them.

That’s a path to burnout and stress, not advancement.

Solutions we can implement today

The stresses and challenges for Black men in tech run deep and the only way to meaningfully address them is to implement strategies and policies that run just as deep. The goal should be to transform the employee experience.

To do that, we’ve identified four areas for organizations to focus on: wellness, including psychological safety and financial wellness; embracing and encouraging participation in employee resource groups (ERGs); an audit of internal talent assessment processes; and mentorship.

Prioritize psychological and financial wellness

At its core, psychological safety is about creating an environment where employees feel comfortable bringing their whole selves to work. This allows them to use their voices and show up for their teams.

In Workhuman iQ’s latest survey report, “The Evolution of Work,” one of the primary influences on psychological safety was an employee working in their preferred work arrangement. For many, that preference was remote or hybrid.

Our interviewees echoed the psychological benefits of hybrid and remote work. “I can be myself without overthinking [when] working remotely,” one told us. Another said, “There is an extra layer of persona that is needed in the office.”

Addressing the specific stress of additional financial responsibilities can start with financial counseling. This type of approach needs to be two-fold. First, making sure the individual is okay and set up for the future is important. But just as important is the community component. Effective wellness counseling in this area requires a knowledge of the employee’s unique financial situation to properly navigate and reduce the stress of it.

A final, overarching goal for improving wellness for Black men is to provide space to be who they are. At several places he’s worked, Kham has brought with him “The Fellowship,” a community that meets for an hour to play music, work together, and talk to one another. The benefits of this type of comradery are compounding and regenerative.

Encourage and recognize participation in ERGs

The community Kham built can come to life in so many ways. One of which is formal employee resource groups (ERGs). ERGs are voluntary, employee-led groups designed to build a sense of belonging at work. These groups are sponsored by the organization to educate and support employees, address inequalities in the workplace, and help lift traditionally marginalized employees.

Employees who participate in ERGs are more engaged and more immersed in the organization’s culture, they’re also more stressed than employees who don’t participate. They take on additional work and without any recognition or appreciation, it can feel as if that effort is for naught.

In our survey, 54% of respondents are involved in an ERG, but just 41% have been thanked for that involvement and the contributions they’ve made and only 31% report their involvement and contributions are even visible to colleagues outside the group. Worse, 12% report that they’ve been treated unfairly by someone in their organization for their participation in an ERG.

Our survey found that compared to employees not thanked for participating in ERGs, those who were reported higher levels of psychological safety, identity safety, and connection along with lower levels of stress and significantly lower levels of identity threat.

As we discussed earlier, when someone hears something positive about themselves it has a powerful effect on their mindset and outlook. That includes something as simple as a genuine “thank you.” ERGs can be a pillar of an organization’s diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) strategy. But only if that experience is positive. Thus, it is in the organization’s best interest to ensure that it is.

Review and improve internal talent assessment processes

Often, most of the diversity found in organizations is found in entry-level positions. The higher up you go in an organization, the more this diversity starts to decrease. Then you get to the most senior level and see almost none. It is my perspective that a broken internal talent assessment process is to blame.

Let me explain. In many organizations, employees get designated as high potential or successors based on a nomination. This nomination affects eligibility for developmental opportunities and promotion. With all the stereotypes around Black men and the resulting lack of psychological safety, is it any wonder that Black men are less likely to be considered high potential or as a successor for a senior level role?

Let’s take a step back and talk about performance evaluation and its biases. According to 2023 Textio researchOpens in a new tab, Black and Hispanic men are the least likely to be told that they are brilliant or genius. The most likely? White and Asian men. Obviously, this is affecting who a company is designating to be their future leaders. What about more basic feedback? Well, Black men are suffering there, too. According to this same research, Black men are the least likely to get actionable feedback.

Though the situation seems bleak, there are steps you can take right now. Let’s start with feedback. As a people leader, ensure everyone in your organization gets great feedback. That creates a level playing field for all employees.

In practice, this looks like avoiding superlatives. Especially with negative or constructive feedback. No one always or never does something. Come on now. Give a specific example of when the person demonstrated a particular behavior and the impact of that behavior, and work with the employee to agree on a different behavior that works.

Avoid giving feedback about personality. Someone can change their behavior with enough motivation and diligence, but please don’t ask someone to change their whole personality for you and your organization. Where feedback is concerned, focus on the behavior, the impact of the behavior, and the change that needs to be made. Every time you see that change, recognize and celebrate that moment to make it stick. That is a recipe for growth.

Speaking of recognition, recognition should be part of your feedback strategy and it works even better if this happens within a formal program. Here’s why.

Let’s get back to the topic of how an organization decides if someone is a high potential or a successor employee. Did you see my italics when mentioning the nomination process? That’s because I hate it. Sorry. The disdain is real. I think it’s rubbish and invites the biases we see in performance feedback to flourish and have a wider and more negative impact. Chuck it and stop it.

Imagine a better world with me instead. Imagine if you had a robust recognition and performance feedback practice. Black men are getting high-quality, actionable feedback like everyone else. Recommended behavioral changes are clear and agreed upon between leader and employee. When the employee makes the change, the manager and the employee’s peers recognize it, and this recognition shows up on a social feed for others to celebrate.

And then, stay with me here, when it comes time to decide who is a high potential or a successor, you harness the wisdom of the crowd and mine your recognition data to see who the organization values for what and match that to the needs of your organization’s roles and future.

I’m writing this so you can’t see it, but mic dropped. I’m walking away. You should totally do this. I promise you it’s a better way.

Provide mentorship

Earlier, I mentioned the power of positivity and what it can do for an individual. One of the more impactful sources of that positivity in the workplace comes from mentors. From mentorship springs encouragement, empowerment, and exhilaration of someone believing in you.

Just 37% of our survey participants reported having a mentor at their current organization. These participants had higher levels of psychological safety and connection and were more secure in their racial identity at work.

On the heels of a discussion about a lack of diversity at higher levels of an organization, it’s important to note here that mentors for Black men in tech do not have to identify as Black. In fact, that was the case for 70% of the respondents who said they had a mentor.

You don’t have to be a Black person to help a Black person. Numerous times we heard stories from our interviewees about people of a different race advocating for them and making a tangible difference in their lives and careers. Be that person for someone else, regardless of your race and ethnicity. Just do it.

Conclusion

I am writing about this research and experience for many reasons, but I can narrow it down to two. First, these stories need to be told. It is vital for any organization hoping to improve their DEI efforts to hear the full scope of what Black men experience at work. Without an understanding of the depth of the issues and challenges they face, it’s near impossible to meaningfully address them.

The second reason is this research is incomplete. To draw more concrete conclusions and expand our own knowledge, we need more Black men to take this survey. Working against us are the distrust and hesitancy to participate as well as the simple truth that there aren’t that many Black men in tech to begin with.

For that reason, I want to end with a call to action to spread the word about this surveyOpens in a new tab. Please share this with your communities, your LinkedIn, wherever. We are eager to expand on our research and share more stories of the Black experience in tech

About the author

Meisha-Ann Martin, Ph.D.

Dr. Meisha-ann Martin is the senior director of people analytics and research at Workhuman. She has a personal passion for diversity, equity, and inclusion and loves using data and analytics to identify and remedy inclusion gaps in the employee experience.

Meisha-ann has a Ph.D. in industrial and organizational psychology based on her research on diversity attitudes in the workplace and has fifteen years of experience working in people analytics and employee engagement across a variety of different industries.

Meisha-ann hosts Workhuman's podcast How We Work, she regularly speaks at conferences and on webinars and her thought leadership has been featured in Forbes, HR Dive, and Benefits Pro. HR Executive named her one of the top 100 HR Tech Influencers in 2023.

She is considered a people analytics/employee experience expert as she has led these efforts in companies like Flex, JetBlue and Raymond James Financial and is the former head of talent experience at ServiceMaster.